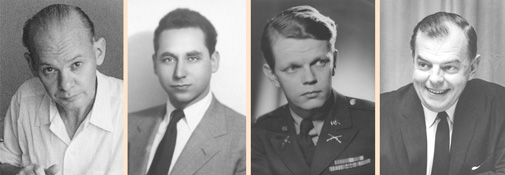

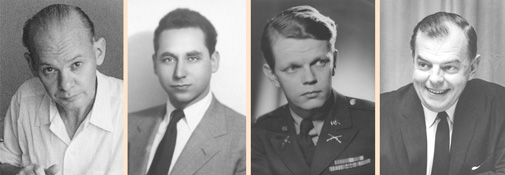

The men who ran the Marshall Plan Motion Picture Section in Paris strongly believed in the potential of film to effect social change. Hemsing profiled Lothar Wolff, who had been picked to set up the film division, and the rest of the team: “German-born, [Wolff] had been the long-time chief film editor at The March of Time and in 1948 had produced Lost Boundaries for de Rochemont, a pioneering feature film about black-white relations in America… His philosophy, his amiability, his skills and keenness in organization, all left an indelible stamp on the unit. Wolff understood how to address European audiences. His deputy and successor, Stuart Schulberg, had been recruited from American military government in Germany in 1949, where [as head of the Documentary Film Unit, Information Services Division, OMGUS, Berlin] he had produced the feature-length official record of the Nuremberg trials of Nazi war criminals. Schulberg, born in Los Angeles in 1922, was the son of B.P. Schulberg and brother of the writer Budd Schulberg; his Swiss schooling explained his fluent French and German…The newly named deputy was Nils Nilson, who had moved up from ‘third man’ of the unit. Son of a Swedish father and German mother, Nilson, then 32, had also served with the American military government in Germany, [as Deputy, Information Services Division, OMGUS, Munich]…These musical chairs landed me in the ‘third man’ slot and soon deputy, then acting chief during the last years before I closed down the operation in 1955.”

This team, backed by screenwriter Jimmy Shute, recruited talented filmmakers from all over Europe. Some were already accomplished; many were young and inexperienced. Some of the names we know – Bachmann, Batchelor, Baylis, Borgerson, Brusse, Connor, Curtis, De Goldschmidt, Elton, Erbi, Freedland, Gallo, Grimblat, Halas, Kiepenheuer, Klotz, Kurland, Leenhardt, Legg, Luft, Mackie, Marcellini, Nash, Niederreither, Radvanyi, Rodes, Sandoz, Secondari, Stapp, Sussman, Tressler, van der Horst, Vicas, Vitrotti. Many others were never credited.

It is tempting to look back upon the Marshall Plan as a halcyon time, but recent scholarship reveals a more tumultuous truth. As Tom Wilson, one of its top administrators, recalled: “for the first few years, France was the strategic center of a knockdown, drag-out battle between the friends and foes of the Marshall Plan…Against all this, the Marshall Plan information office in Paris responded with an unprecedented output…It was a strenuous contest but one that was never in doubt.”7

The men behind the Marshall Plan information and film sections were too busy doing their jobs to stop and document their historic mission. As Hemsing recounted: “All of us working with the Marshall Plan in those days felt, somewhere inside ourselves, that we were making history—helping restore a Continent and articulating its citizens’ desire for a new united Europe. Yet how little of that history has been recorded in terms of the workings of the Marshall Plan—not just its origins and accomplishments. Our ‘emergency operation’ never appointed an official historian—hence there was no log of events; even basic documents are now lost or hard to come by.”

But even if most of the textual evidence is lost, at least the films live on.

Sandra Schulberg, U.S. Project Director, Selling Democracy